Earth month dialogues: No story is too small

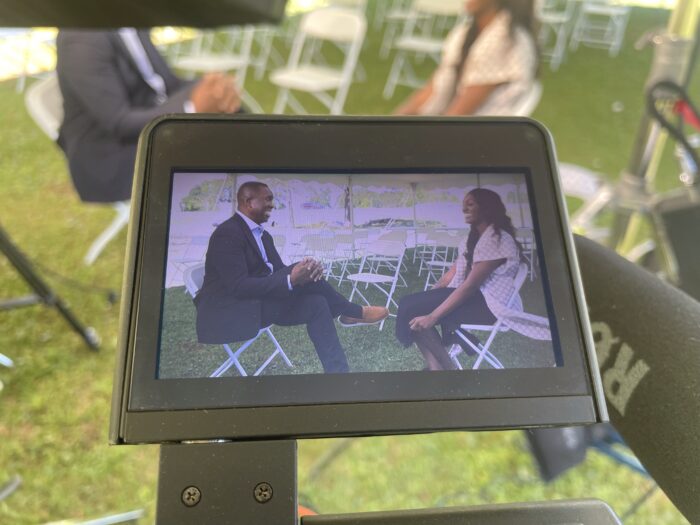

“I’m basking in the moment,” said Steve Osunsami, a senior correspondent with ABC News. “Sometimes you have to stop and enjoy it.”

Osunsami came to Charlottesville, Virginia, with two colleagues to accept this year’s Reed Environmental Writing Award. The three-person investigative unit also included ABC News producer Jared Kofsky and data journalist Maia Rosenfeld, whose award-winning storytelling captured America’s attention and gave viewers a window into the racist history of highway flooding in smalltown Alabama.

When it rains, it floods in the close-nit Shiloh community on the outskirts of Elba. A controversial highway widening project has elevated the road higher than the rooftops, and now even the slightest amount of rain can cause major issues for families who live there.

Shiloh Pastor Timothy Williams invited ABC to experience the flooding for themselves and meet another special member of their community – Dr. Robert Bullard, who is known as the Father of Environmental Justice. There’s still work to do, but together, reporters and residents took an issue that was getting overlooked locally to a national stage.

“I don’t think any of us expected to be recognized in this way and I’m having an emotional moment,” added Osunsami, sitting between Rosenfeld and Kofsky. “It’s my pleasure to be here with you two to celebrate our amazing and impactful work.”

Keep reading for our lively conversation about the high stakes in Shiloh, its rich history, and the unique skills each journalist brings to the table.

Editor’s note: This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Describe your first impressions of Shiloh.

Maia: Something very special is happening there. I was in awe that this community has stuck together through 150 years of history. The families that live there have passed down their homes and their properties since the end of slavery and it was really powerful to see how much it means to them. It makes the story much more poignant and compelling.

Steve: I won’t lie, I came onto the story last, and I was surprised we were covering it. I thought it was too small of a story for us. Something changed while writing it and I realized it’s the exact story we need to be telling because no one else is going to.

Jared: Doing journalism around Charleston for two years after college was a tremendous help in getting ready for this story. Even though Alabama and South Carolina have a lot of differences, there’s a lot in common between two rural communities in the South dealing with highway expansion.

How did you find this story in rural Alabama?

Jared: This all started with a voicemail from Pastor Timothy Williams, who called us out of the blue and said, “My neighborhood is flooding, we have a lengthy history here, and we don’t want our community to be washed away.”

It struck me as different from the kind of calls we typically get. I called him back, one thing led to another, and he told me, “You have to come down to Shiloh to see it for yourself.”

I went down there and brought a camera crew. It started raining. You could see all of the water pouring down from this highway into this community.

How was it seeing the Shiloh flooding for yourself?

Jared: I got absolutely drenched walking in floodwaters and I experienced why people are so afraid of losing their homes and property damage. I also learned they don’t want to leave their community.

Then I went back three more times. I brought Maia and Steve, and we were able to take a deep dive into this small community that otherwise might not have gotten tons of national attention.

Steve: This community wasn’t getting into the local newspaper. For them to call a network, and for a network news operation to send this resource, is incredible.

How did the network ultimately greenlight this story in smalltown Alabama?

Jared: At the ABC News Investigative Unit, we want to know what went wrong and why. We brought in public records, sending as many public records requests as possible. We analyzed thousands and thousands of pages.

Maia did a great data analysis of the weather data showing this area is not a flood zone. We have flooding in oceanfront and riverfront communities, but it’s a big deal that this community doesn’t ordinarily flood. It only became widespread after the highway was widened.

Maia: I took a look at FEMA flood maps and saw this community isn’t in a flood zone, but I also knew from some other data stories I’d worked on that, because of climate change, flood risk has been changing. FEMA’s flood maps don’t always keep up with that change, so we had to look at forward-looking climate modeling data.

It showed that there was only a 4 percent chance of flooding on these properties in Shiloh at least once a year. It had been five years since the highway was built and it had flooded every year, nearly every time it rained.

NOAA data on precipitation showed heavy rain more than 150 times since the highway was built, so that helped us establish that this wasn’t natural. Looking at the documents Jared gathered, we found really questionable legal maneuvers by the state to protect themselves instead of protecting their residents.

Jared: One thing led to another, and once Steve was on board with the story, we knew we could really make this resonate with people. Steve does a great job of taking stories that might seem very complex and making them relevant and accessible to a national audience.

I would love to hear more about the collaboration between you three.

Maia: We each bring very different and complementary skills to the table. Like Jared was saying, Steve took the story and made it sing. I analyzed the data.

Jared picked up the phone and had the instinct to know it was a story he wanted to follow. He got the rest of us on board and the buy-in from the higher-ups at ABC, which is really important for getting the resources we needed to go down there. Jared also did a lot of digging up files and making records requests.

Steve: We uploaded all of the video we captured. I like to see everything. I like to listen and hear every single thing that we captured. Then I will write.

Do you have tips for telling stories like yours as fewer journalists are able to?

Steve: Journalism as a whole is going to have to get more creative.

People are going to have to find new ways to do stories like these. I’m just not convinced the answer is going to be Twitter or the internet.

I started in 1997, and I have hope when I look at all the changes since then. For example, everything that Maia does is wild. Data didn’t exist in the same way back then. Everything was on paper. We had binders. We would get microfiche and go to the libraries and print out magazines. That’s how we did research.

Maia: It’s changing even more with AI.

Steve: AI could end up being a great tool to help facilitate and make journalism easier and less costly to do these kinds of stories. As much as we’re afraid of it, it could be helpful.

Maia: Absolutely. You can use AI to help organize your tasks. It’s never creating the end product – it’s helping you skip some steps in your journalistic process.

Jared: On the one hand, this story is a very old-fashioned kind of journalism: knocking on doors, using public records, interviewing face-to-face. But we were also able to leverage the power of new technology and journalism to tell this piece, ranging from Maia’s data analysis to a database that made all the public records we collected searchable.

Maia: These were scanned PDFs. We made our own little index of interesting stuff, including a poorly scanned document of what construction workers were saying while building the highway. It came up in some of the documents that they had residents coming alerting them about the flooding. It even mentioned Pastor Williams by name.

Steve: I’m learning stuff right now that I didn’t even know was happening. Wow. It was a very important line in the story that this wasn’t new, that the minute they started the construction, residents started noticing a difference and complained about it. This is just the first that I’m learning how that came about.

Steve, we heard you had a full circle moment while working on this story.

Jared: Tell the story.

Maia: It’s a great story!

Steve: When I was in college, I competed in forensic speech competitions. My main event was called Persuasion Oratory, and in my last year of college my oratory topic was environmental racism. I took second in the country with it.

The speeches you give are researched with citations. At the top of my speech, I told a story from a book called Dumping in Dixie that was written by Dr. Robert Bullard.

I have since told him this story but I think I was more excited than he was.

Let’s end with the big takeaways. What did you learn from telling this story?

Maia: What sticks with me is the risk residents took by talking to us and the real consequences they faced. It taught me the value of sharing their story.

Jared: And it taught us the importance of being willing to take risks in our reporting.

Steve: My biggest takeaway is no story is too small.